A little over a year ago, I read an article on CNN about stock photography. As someone who considers my photography to be a bit more “artistic” than mere stock photography, I initially dismissed the idea that any of my pictures would be considered low enough for “stock” photography. This being said, my photos over on Fine Art America weren’t selling, so I wasn’t attracting the artistic crowd to my photographs. Sure, I know there’s a particular art (har har) to metadata tagging and keywords. Also, considering the price for any of my artsy photographs was probably a little high, and my reasonably limited portfolio, I knew I wasn’t going to make much money in the fine art market.

I finally decided to swallow my pride.

With my artistic photography not attracting any sales, I finally decided to swallow my pride in 2018 and dive into the world of stock photography. Fortunately, I already had a pretty extensive portfolio of photographs, so I could immediately start uploading pictures to a variety of stock photography sites. Unfortunately, most of the photos in my collection had watermarks, so I needed to go back and re-edit some of the more popular ones before I uploaded them. While this took a little bit of work, the best part of stock photography is that once a photo is uploaded and accepted, it’s able to generate revenue. There are some pretty odd stock photos out there, so you never know what people will need that your pictures can satisfy.

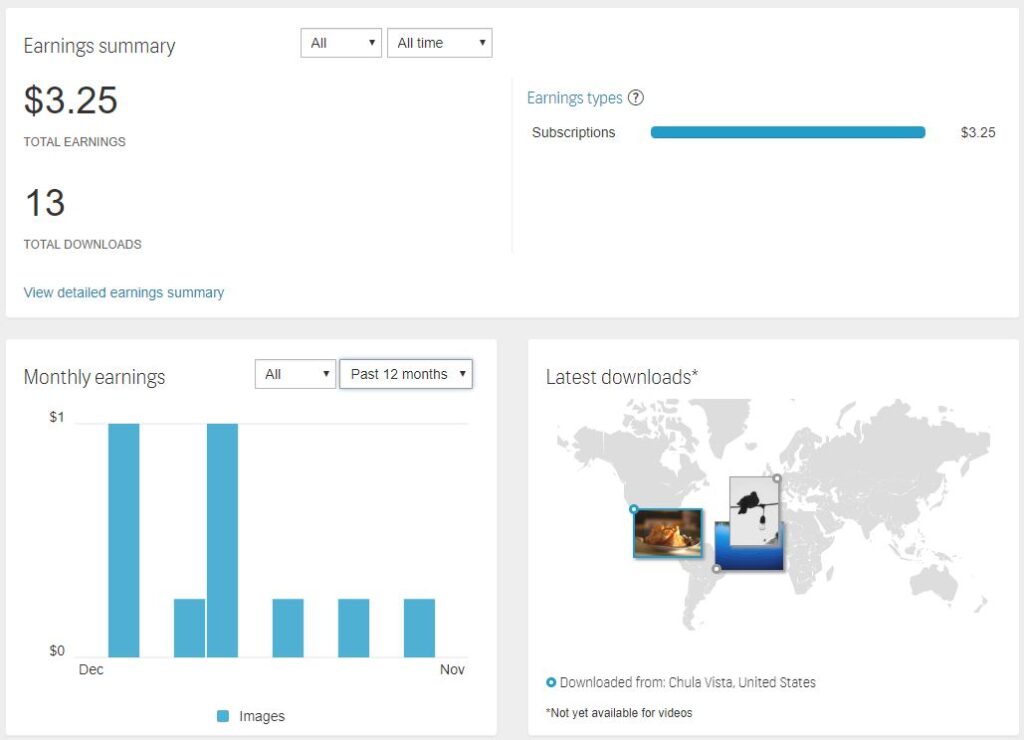

Now that we’re in 2019, I have some data for a year’s worth of stock photo sales. In that same timeframe, I don’t think I made a single sale on Fine Art America. However, while it’s not a huge amount of money, it’s still something. Perhaps I’ve been taking stock photos all along and just never realized it. At any rate, the first two sites I signed up on were Shutterstock and Adobe Stock. I’ve also been accepted into Getty’s iStock site, but I haven’t had the time to get most of my photos ported onto their platform yet. Let’s look at the results from Shutterstock first:

As you can see, I didn’t make many sales with Shutterstock over the last year. I think part of this is due to how Shutterstock will usually accept every picture I upload to their platform. Consequently, if they do that for me, they’ll do that for other photographers as well. With so many pictures to sort through, I think most people will have trouble finding my pictures without the right keyword tags. Still, selling 13 pictures this year is admirable. Here are the top five of those sales (that constituted 8 of the total sales):

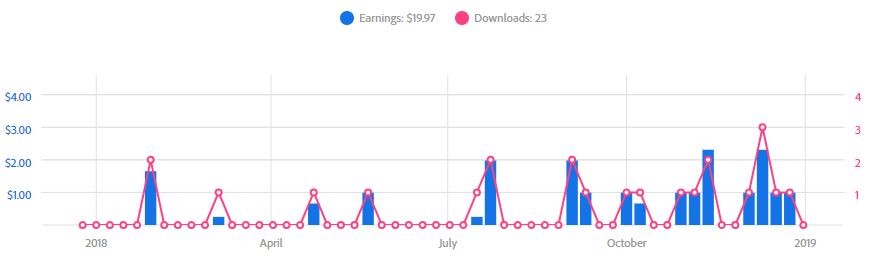

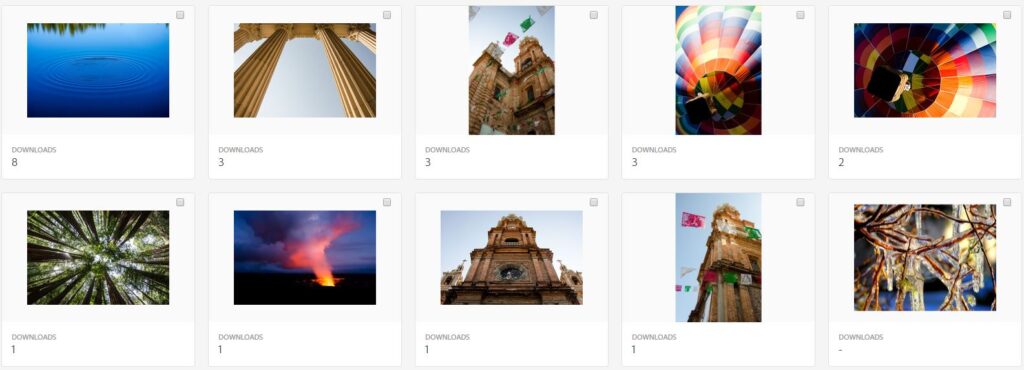

Sure, I only make $0.25 per sale on Shutterstock, but it’s clear that I have at least one photograph that’s pretty popular. I kind of want to see what people are using “Ripples on a clear lake” for, but I’m fine with the occasional sales of it. Now, on the other side of this stock photo landscape, we have Adobe Stock. They’ve been a little more discerning when they accept my photos. Consequently, while I’ve had fewer photos successfully accepted onto their platform, they’re definitely of higher quality. I think this has helped with sales on Adobe’s site, since there are fewer photographs to choose from, but they’re all a lot better than sifting through a bunch of so-so pictures. Here are the stats for this year for my Adobe Stock sales:

Clearly, I’ve made a lot more money with Adobe Stock than I have with Shutterstock. I’ve also sold more on this platform, with the sales coming more regularly as my successful sales are likely driving search engine results. Another plus to Adobe Stock is that they have generally paid up to $0.99 for each photo sold (sometimes it’s less, but it’s been rarer), which is why I’ve earned significantly more with Adobe than with Shutterstock. If we look at what photos were my best sellers on this platform, we’ll see a similar trend to the pictures on Shutterstock:

Once again, my “Ripples on a clear lake” has garnered another 8 sales, but interestingly enough, I’ve also had multiple sales of two different views of a hot air balloon, as well as a church located in Puerto Vallarta. There’s definitely a “look” to the stock photos of mine that have sold, and now when I edit new pictures, I can usually tell if it would be a potential stock photo. In any case, these photographs that have already sold will still remain up on both websites, likely garnering me more sales in the coming days and months and years.

So, what did my relatively successful foray into stock photography teach me in 2018? First of all, it’s easy to dispense with your pride when you get regular e-mails informing you that you’ve sold another photograph. If anything, it’s incredibly affirming: someone out there needed my picture enough that they paid for it. It might not be a lot, but the concept of stock photography is firmly rooted in the long game. The more pictures you have in your portfolio, the more potential sales you could have. The sooner you get those pictures uploaded, the sooner potential customers might find them. I do have quite the backlog of pictures to upload and tag, but hopefully, I’ll be able to get them up in 2019 to help me earn just that much more. And it’s not like I have to actively work on the photos that are already accepted: it’s truly a “set it and forget it” venture.

In conclusion, if you think stock photography is “lesser than” other types of photography, ask yourself: how many sales have you made this year with your more “artistic” pictures?